The Bible Didn’t Fall From the Sky: How Canon, Politics and Translation Shaped the World’s Most-Read

The Bible was formed over 1,500 years, with different canons, royal politics and human choices. Understand this history without losing faith or clarity. (spiritual)

✍️ Autor: André Nascimento

1/13/20264 min ler

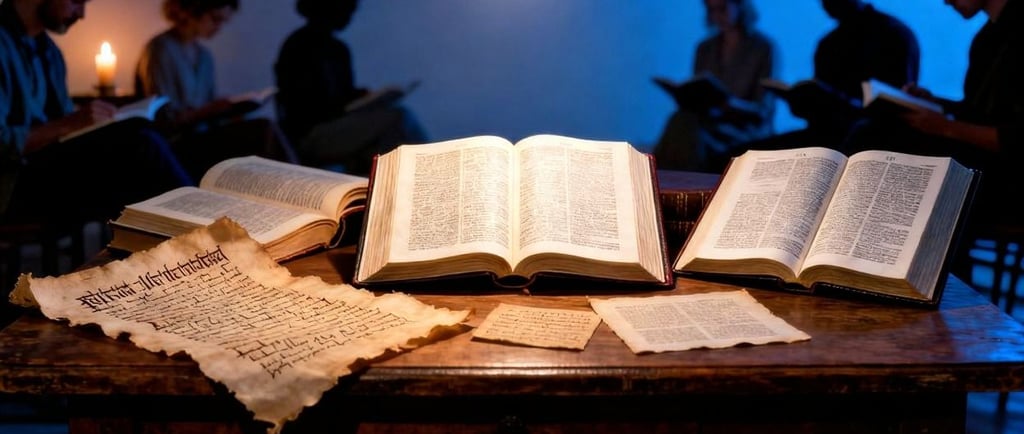

1. The Bible is not “a book”, it is a library

Bible as collection of books

The word “Bible” comes from “biblía” — books. Instead of a single volume, it is a collection of texts written in different eras, languages and cultural contexts, gradually gathered into one corpus.

From Genesis to Revelation, we are dealing with a spiritual and historical library: narratives, poetry, laws, letters and visions, passed down through Jewish and Christian traditions over many centuries.

2. Timeline: from Genesis to Revelation ⏳

biblical books chronology

Scholars generally agree that the texts we now call Genesis and the rest of the Pentateuch reached their final form around the middle of the first millennium BCE, even though they preserve much older oral traditions.

Revelation, by contrast, is a first‑century text often dated between 70 and 100 CE — written more than a thousand years after the earliest layers of Old Testament literature. In other words, the Bible is the product of roughly 1,500 years of writing and redaction, not a single moment in time.

3. The Ethiopian Bible: the largest and oldest Christian canon 📜

Ethiopian Bible 81 books

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church preserves one of the broadest traditional biblical canons, with 81 books (and up to 88 in some counts), including works like Enoch, Jubilees and 1–3 Meqabyan (Macabees‑like books) that do not appear in Protestant Bibles.

The Garima Gospels, ancient illuminated Ethiopian manuscripts, are dated to around 1,500 years ago and rank among the oldest surviving Christian codices. This shows that the idea of “one single Bible” is recent; different churches have preserved different lists of books.

4. Catholics, Orthodox and Protestants: different canons ✝️

differences in biblical canon

The Roman Catholic Church recognizes a canon of 73 books (46 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New), including deuterocanonical books such as Tobit, Judith, Wisdom and 1–2 Maccabees.

Most Protestant traditions, influenced by the Reformation, adopted a canon of 66 books, moving the deuterocanonicals to a separate “Apocrypha” section or omitting them from common editions. Eastern Orthodox churches maintain slightly broader canons, with variations depending on each tradition.

5. The 1611 turning point: the political project of the King James Bible 🇬🇧

origin of King James Bible

In 1604, at the Hampton Court Conference, King James I of England authorized a new translation of the Bible into English, published in 1611 as the King James Version (KJV). One aim was to replace the popular Geneva Bible, seen as politically troublesome, and to provide a text that could serve both the Church of England and certain Puritan factions.

The KJV was produced by committees of scholars working from the Hebrew and Greek manuscripts available at the time, revising earlier English versions. It went on to become one of the most printed Bibles in history and heavily influenced many later translations, including some used in Portuguese, directly or indirectly.

6. Not “Catholic” and not “original”: the Bible most people read today

Protestant Bible 66 books

Most Bibles used in evangelical contexts follow the Protestant 66‑book canon, aligned with Reformation theology, not the Catholic 73‑book canon and not the Ethiopian 81‑book canon.

Although modern translations are based on Hebrew and Greek critical editions, they also carry historical marks from the English tradition (such as KJV influence) and from translation committees with particular theological lenses.

7. The Bible has never been “just history” or “just dogma”

Bible as historical and spiritual text

The popular phrase “the Bible is not a history book” is both true and false. It contains historical narratives, but it was not written with modern academic historiography methods; its main aim is theological, spiritual and identity‑forming.

At the same time, treating it only as a set of timeless decrees without historical context produces shallow and sometimes harmful interpretations. Holding both sides — sacred text and situated document — leads to a more honest reading.

8. The risk of forgetting human choices 🧩

canon formation human decisions

Canon formation involved councils, debates, power struggles, political contexts and very concrete human choices — what went in, what stayed out, what was called “inspired” and what was labeled “apocryphal”.

Ignoring this opens the door for claims that one specific printed edition is “the only true Bible”, while erasing the fact that other ancient Christian traditions have equally old but different canons.

9. Call to action: read with faith… and with your brain 📖🧠

reading the Bible with critical awareness

If a thinker like Augusto Cury could send a message to billions of people, it might be: “Do not hand your mind over ready‑made to any narrative, not even a religious one.” Reading the Bible deeply today requires two simultaneous attitudes:

Spiritual respect: receiving the text as a source of meaning, ethics and encounter with the divine.

Historical awareness: remembering there were languages, copyists, translators, kings, councils and different editions across 1,500 years.

💬 Invitation: Next time you open your Bible, ask yourself:

“Which tradition did this canon come from? Who decided these books would be here? What books exist in other Bibles that I’ve never even read?”

This curiosity does not destroy faith; it prevents your faith from being infantilized.

10. Conclusion: faith is divine, the book is human — and that is not a threat ✝️📚

human and divine dimensions of the Bible

The Bible is an encounter between spiritual experience and concrete history: a God who speaks through ancient languages, specific cultures, power struggles and editorial decisions. Remembering this does not make the text less sacred; it keeps us from turning it into a rigid idol detached from its own story.

Once we recognize that there are Bibles with 66, 73 or 81 books, that King James’s project strongly shaped what many read today, and that canon was a process, we become less hostage to narrow interpretations and more open to a mature faith capable of dialoguing with history and with difference.

Constructive critique🧐

The conclusion rightly highlights the tension between the divine and human sides of Scripture, but it may feel abstract to readers looking for concrete application: “What do I actually do with this?” It offers few direct examples of how this understanding could change preaching, devotional reading, family discussions or respect for other Christian traditions.

It may also unsettle readers who have never heard of the Ethiopian canon or deuterocanonical books, without providing clear, safe pathways for further study.

To strengthen it, the article could:

recommend accessible introductory books or videos on canon history;

show how this knowledge can reduce needless doctrinal fights;

stress that this is not about “relativizing everything”, but about grounding trust in the Bible more honestly.

Contato

Apoio e dicas sobre saúde mental.

Redes

+55 11980442159

© 2025. All rights reserved.